A core component of our infrastructure is the remote procedure call (RPC) system. It lets our microservices communicate with each other over the network in a scalable and fault-tolerant way.

Whenever we're assessing our RPC system, we look at a few key criteria:

High performance 🐎

Communication between services should be as fast as possible. The RPC subsystem should add minimal latency overhead and avoid failing replicas when routing requests.Scalability 📈

Our platform sees tens of thousands of requests a second and these numbers continue to rise as our user-base grows. Any subsystem we have needs to continue to support this growth.Resilience 💪

Service replicas die, bugs happen, networks can be unreliable. A subsystem which has support for detecting unavailable downstreams and detection of outliers let the system react and route around failure.Observability 🔧

The RPC subsystem generates a lot of data on the performance of our platform. Integrating with our existing metrics and tracing infrastructure to expose service mesh information alongside our existing service metrics and tracing.

In 2016, we blogged about building a modern bank backend and a key part was our service mesh powered by Linkerd 1.0. When we chose Linkerd 1.0 in 2016, the service mesh ecosystem was relatively young.

Since then, many new projects have iterated on the idea. We wanted to reassess whether Linkerd 1.0 was the correct fit for us.

The service mesh

Our microservices perform tens of thousands of RPC calls per second over HTTP. However, to make a reliable and fault tolerant distributed system, we need service discovery, automatic retries, error budgets, load balancing and circuit breaking.

We want to build a platform which supports all programming languages. While the majority of our microservices are implemented in Go, some teams choose to use other languages (for example, the data team writes some of their machine learning services in Python).

Implementing these complex features in every language we use imposes a high barrier to entry when we want to use something new. Additionally, changes to the RPC subsystem would mean redeploying all services.

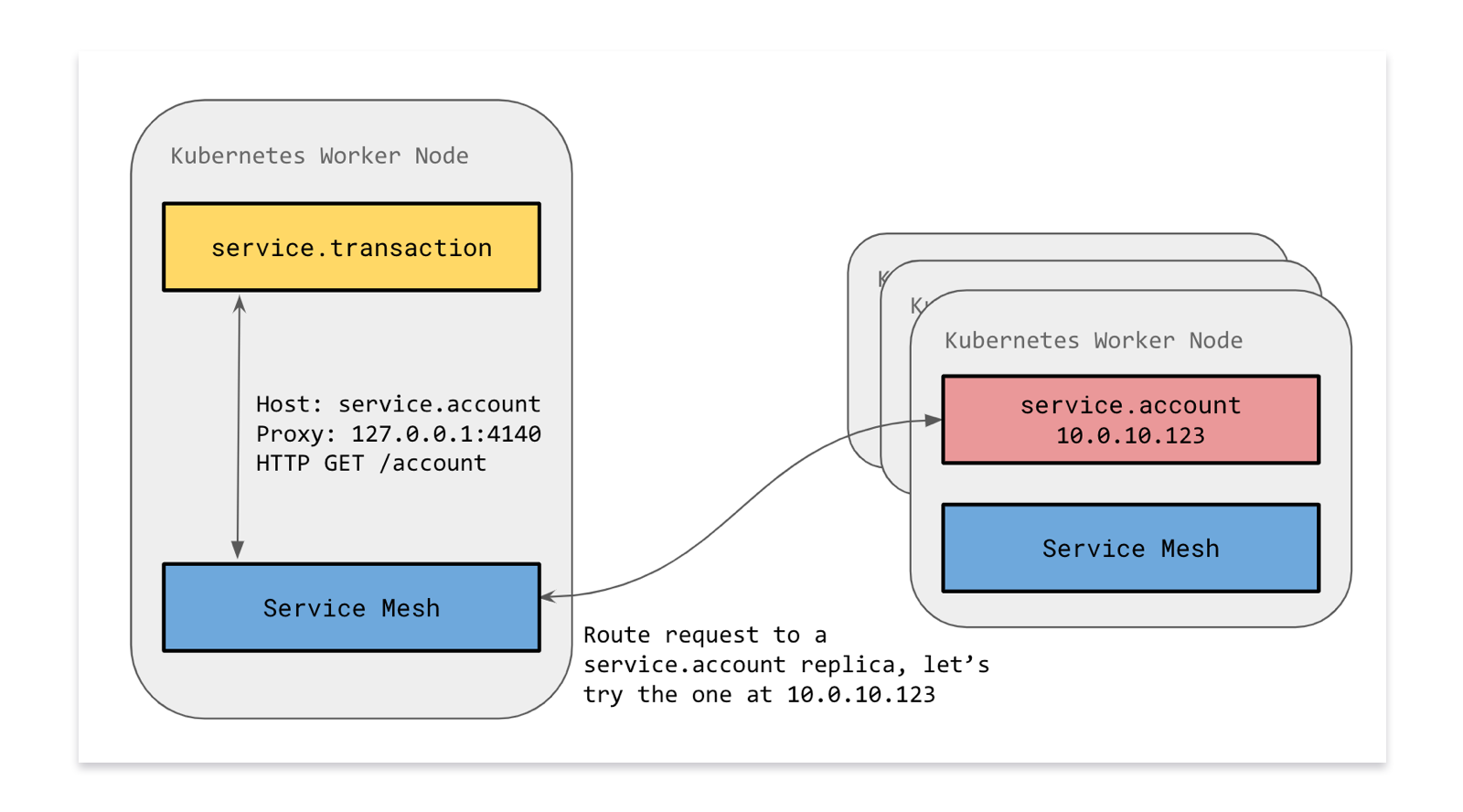

One key decision we made early on was to keep this complex logic out-of-process wherever possible: Linkerd provided many of these features transparently to services.

We ran Linkerd as a Kubernetes Daemonset. This meant that each service would communicate to a local copy of Linkerd running locally on each node.

Migration to Envoy

During our preparation for crowdfunding, we found that Linkerd wasn't able to handle the load without giving it disproportionate amounts of processing power. We had to scale out our infrastructure significantly to cope. As we continue to grow, the amount of resources needed to run our RPC infrastructure was not sustainable. Even during normal load patterns, Linkerd itself was the main factor contributing to 99th percentile latency.

We started evaluating alternatives which would match our RPC subsystem criteria. We looked at Linkerd 2.0, Istio, and Envoy. We eventually settled on Envoy because of its high performance capabilities, relative maturity, and wide adoption in large engineering teams and projects.

Envoy is an open-source high performance service mesh originally created by Lyft. It's written in C++ so doesn't suffer from garbage collection or just in time compilation pauses. It is the core proxy underpinning some of the other projects like Istio and Ambassador.

Envoy doesn't come with any understanding of Kubernetes out of the box. We wrote our own small control plane which would watch for changes in our Kubernetes infrastructure (such as an endpoint changing due to a new pod) and push changes to Envoy via the Cluster Discovery Service (CDS) API so it was aware of the new service.

We used our load testing tools which we built for testing our systems for Crowdfunding to load test the performance of our existing Linkerd setup and a new Envoy setup.

In all our tests, Envoy performed significantly better than our existing Linkerd 1.0 setup while requiring less processing power and memory resources.

There were a few things where Envoy was lacking compared to Linkerd such as latency aware load balancing (rather than just round robin) and service based error budgets (as opposed to just per-request based automatic retries). Ultimately we didn't find these to be dealbreakers though we would like to add them in the future.

We wanted the switchover to be transparent to services. A key factor in our rollout was the reversibility of this change if we needed to rollback.

We set up Envoy to accept and route requests over HTTP just like Linkerd and rolled it out in the same Kubernetes daemonset fashion. We tested the change heavily in our staging environments over a couple of months. Once it was time to roll out to production, we rolled it our gradually over a few days to spot and fix any last-minute teething problems.

Observability

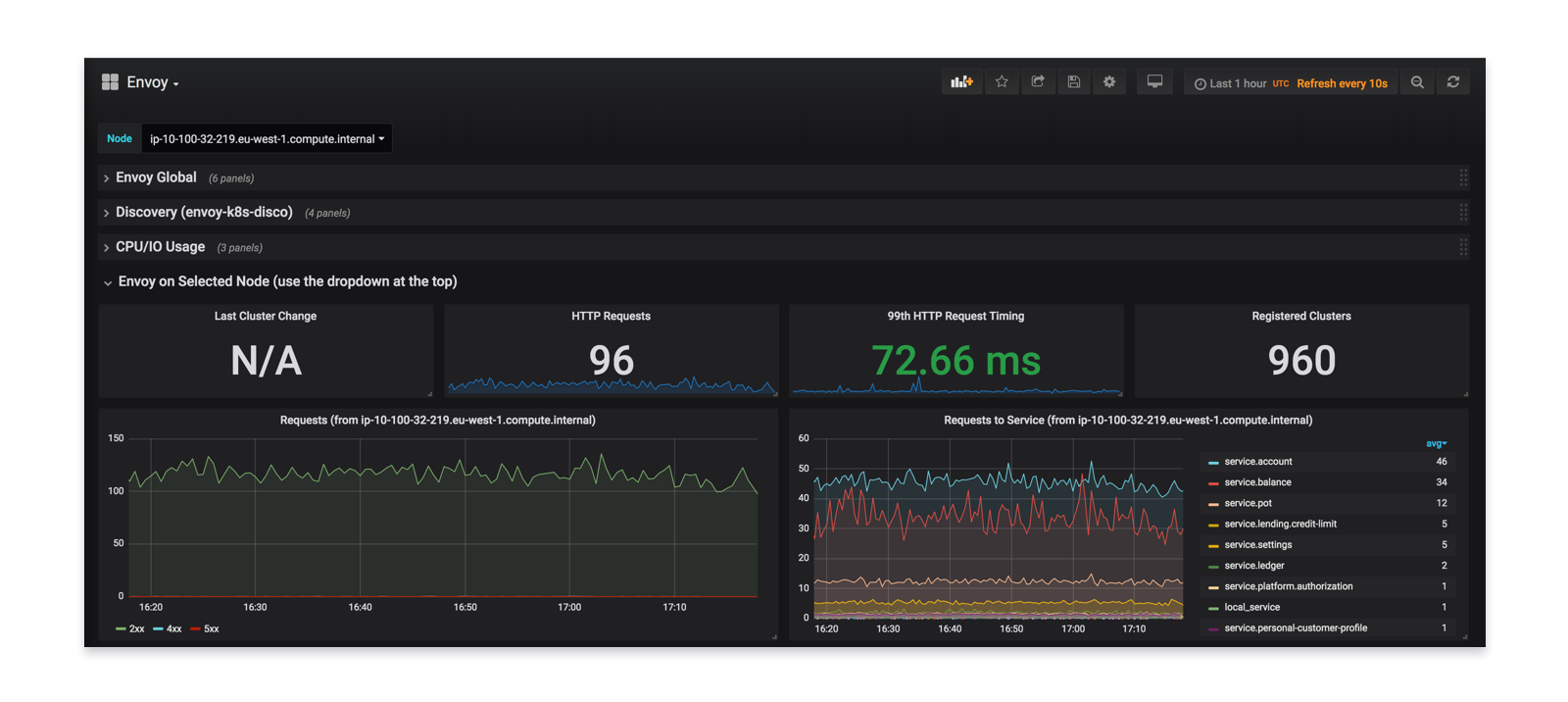

Whilst Linkerd 1.0 had a nice control panel, it didn't integrate well with our Prometheus based monitoring systems. Before we put Envoy in production, we paid careful attention to its integration with Prometheus.

We contributed back to Envoy to finish off first class Prometheus support. This allows us to have rich dashboards to augment our existing service metrics.

By having this data, we gained confidence in our rollout to ensure it was seamless and error-free.

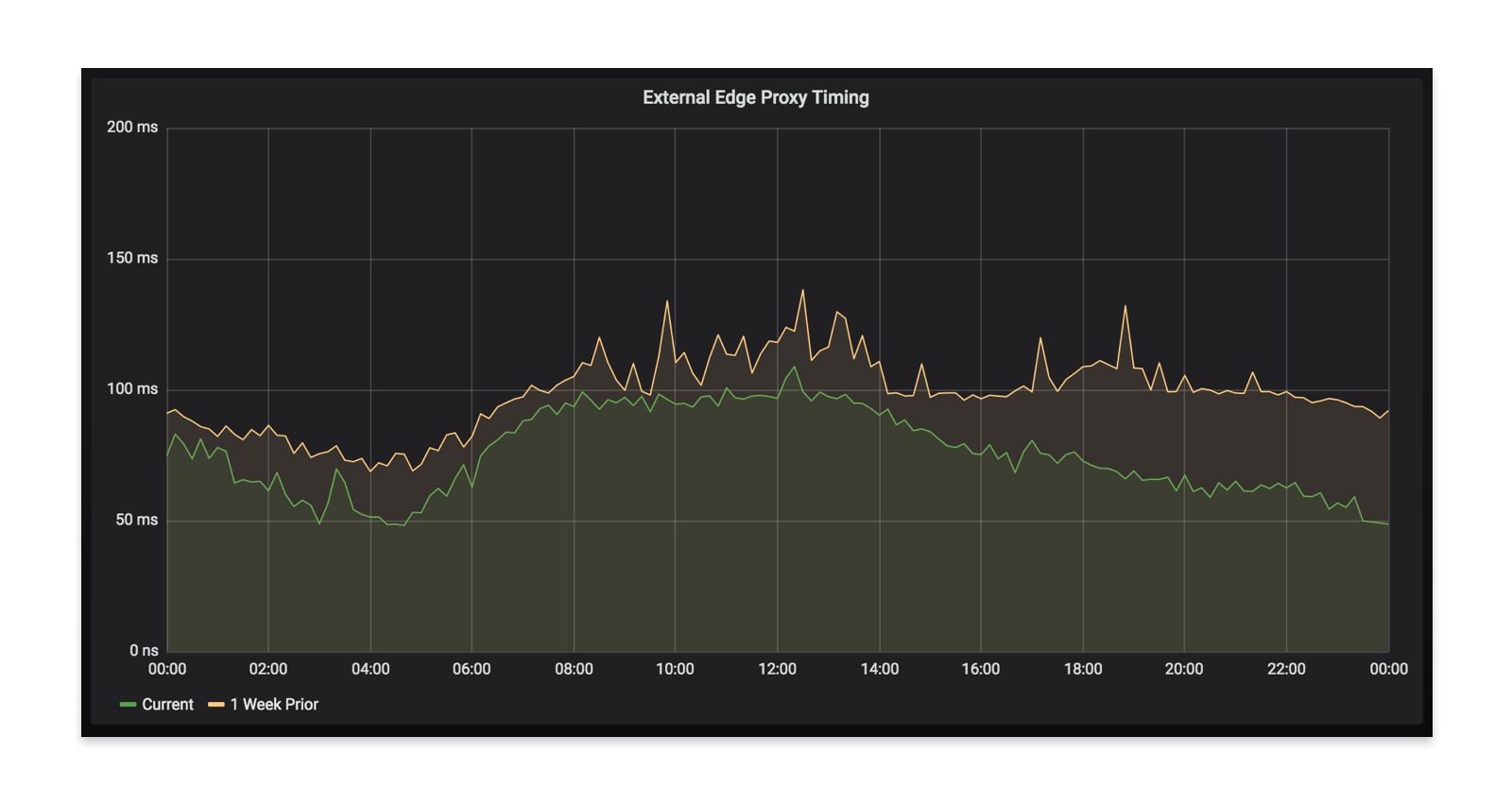

When your app talks to our backend, it goes through our edge layer and then will hit a varying number of microservices (sometimes more than 20) to fulfill the request. As we were rolling out Envoy, we saw a decrease in latency at our edge, corroborating our test results. This ultimately means a faster app experience for everyone using Monzo.

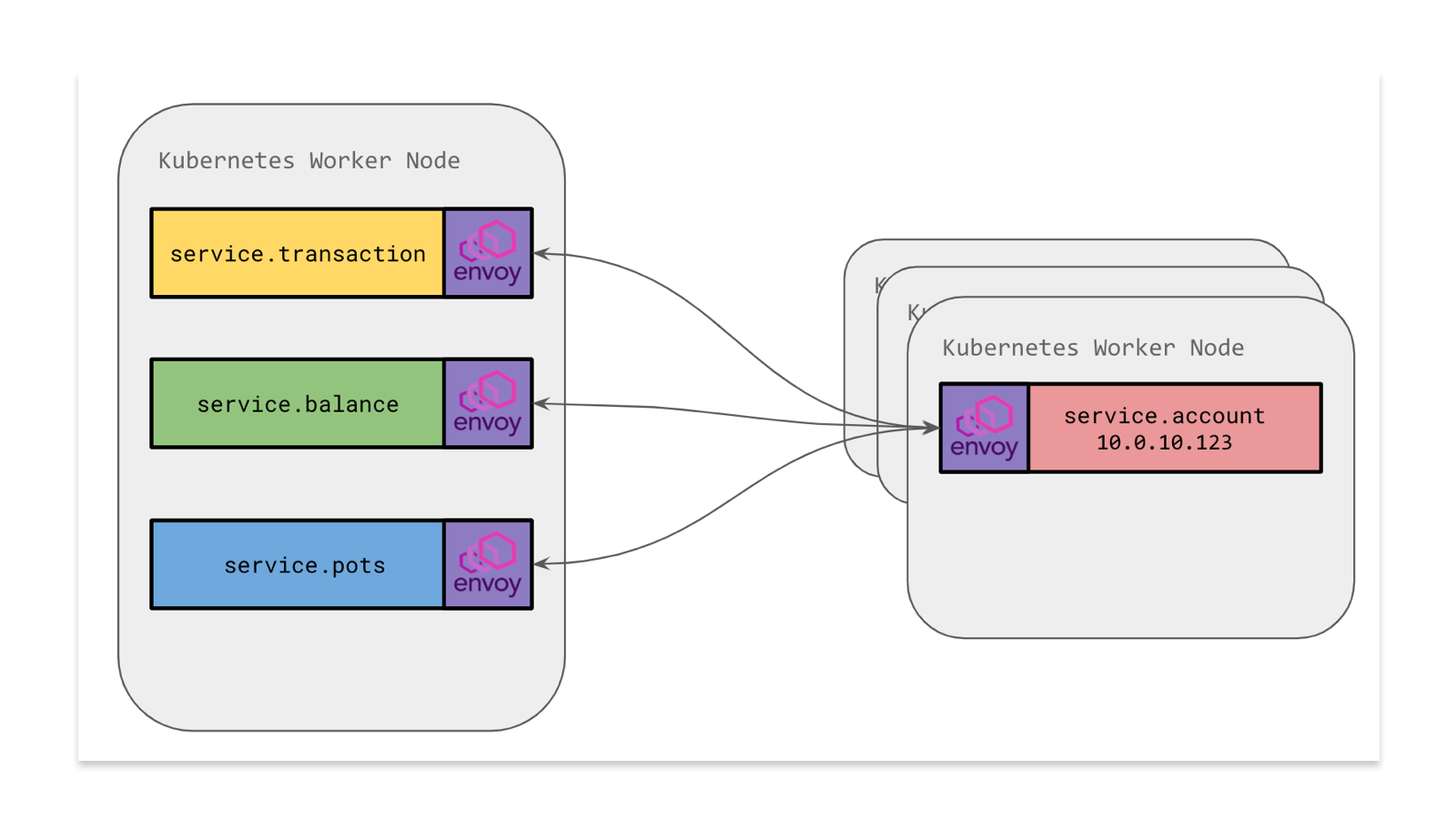

Envoy as a sidecar

A key project we're undertaking right now is moving our services to have Envoy Proxy as a sidecar alongside our microservice containers. This means that instead of communicating with an Envoy on the host (which is a shared resource), each service will have its own copy of Envoy.

With a sidecar model, we set up Envoy to handle both Ingress and Egress. Incoming requests (ingress from another service or from another Envoy) will come in through the local Envoy where we can employ rules to validate the traffic is legitimate. Traffic flowing outward (egress) would go via the sidecar Envoy which is responsible for routing the traffic to the correct place just as before.

A key advantage of moving to a sidecar is the ability to define Network Isolation rules. Previously, we weren't able to lock down sensitive microservices to only accept traffic from certain Kubernetes pod IPs at a network level since traffic came through a shared Envoy. Services had to have their own logic to validate that a request was legitimate and came from a trusted source.

By moving Envoy within the pod namespace, we're able to add Calico Network Policy rules to pods, effectively erecting a network firewall for each of our microservices. In this example, we could say that traffic can only ingress to the service.account pods from a specific defined subset of other microservice pods. This provides an additional layer of security by rejecting unknown traffic at the network level.

A key reason we were able to do this with Envoy and not Linkerd was due to the significantly lower processing power and memory requirements with Envoy. We're now running thousands of copies of Envoy across our infrastructure and this number continues to grow as we roll out Envoy as a sidecar to all service deployments.

What we gained with Envoy

Moving to Envoy has been a great journey. We were able to make this upgrade in place without rebuilding any existing services and gain better insight as a result. We're very happy with the improvements we've seen in resource consumption and latency, and we’re confident that Envoy can support our future requirements as our user base grows.

We're grateful to the Envoy community for the help and support they've given and hope to continue contributing back.

If this kind of work sounds interesting to you, we're hiring for backend engineers and platform engineers!