Because we're a bank, it’s really important that our systems are always running smoothly, so that you can access your money, use the Monzo app, and get in touch with our customer support team whenever you need to.

In the last 12 months we've made Monzo more reliable. But in case things do go wrong, we need to have people ready to restore our service at any time of day. This is the job of the engineering on-call team, who are available 24/7 every day of the year to respond to incidents and put things right for our customers quickly. Whether it’s during office hours, at 2am in the morning, or the middle of a holiday period, our on-call engineers are only minutes away.

Unlike most other banks, we operate a modern technology stack, built almost entirely on public cloud, open-source technology, and a microservice architecture written in Golang. We operate over 700 services in production, running on Kubernetes, and the majority of our state is stored in Cassandra. We also make use of Kafka and NSQ queuing systems to handle the processing of asynchronous transactions.

The rapid growth of our customer base, engineers and services has posed some interesting challenges for operations and on-call. We’ve made a lot of changes to improve how this works, both for Monzo as a company, and for the engineers responsible for supporting it, and we wanted to share what we’ve learnt so far.

Our on-call team

There are two common patterns for on-call teams.

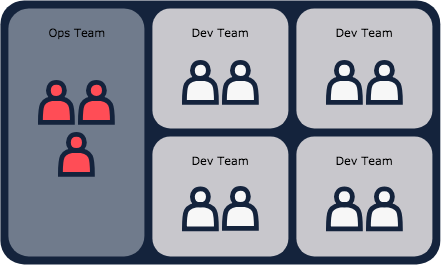

At one end of the spectrum, you can have a central ops team which is solely responsible for on-call and the uptime of a service. One issue with this is that it breeds a tension between teams with misaligned incentives: developers want to make changes and ship new features, while ops want to maintain the status quo to keep things stable.

At the opposite end of the spectrum you can have every team on-call and responsible for the uptime of their services. Typically, this leads to a healthier culture as teams writing software are incentivised to make their services operable. But it does come with some drawbacks: it can be financially costly for the company if you’re compensating on-callers fairly (which you absolutely should be!), and being on-call can also have a strain on engineers’ lives and wellbeing.

Having everyone on-call also poses some specific challenges in high growth companies. When your engineering team is growing rapidly and people are often moving between teams, it can be really destabilising as ownership of services isn’t always clear, and even when it is the cost of understanding a new domain at each change is high. Because of this the overall quality of on-call and incident management can suffer.

At Monzo, we try to take an approach that strikes a balance between both: we have a single on-call team, made up of engineers across all the company.

This means we can operate in a world where teams are incentivised to care, where people across the company advocate for operability, and where the on-call rotation is a great tool for learning and sharing knowledge.

We don’t expect this approach to work forever, but right now it’s letting us iterate quickly on processes and tools, and develop a pattern for on-call which we can roll out more widely later.

How it works

For other companies looking to use a similar system, here's how we practically approach on-call – from scheduling which engineers will do it, to working out how to pay them fairly.

Scheduling to make on-call a little less stressful

Engineers take turns being on-call. We run a weekly rotation that changes over each Friday, and we have a different schedule for office-hours (Monday to Friday, 10am-6pm) and out-of-hours (everything else).

By taking this approach, engineers who have to respond to incidents out-of-hours have some guaranteed time off-call during office-hours. When incidents do happen, this gives them time to recover, and hopefully makes the on-call week less stressful overall.

With this system, managing the schedule is slightly more painful, but the hardest thing is keeping office-hours and out-of-hours on-callers synchronised throughout the week. We address this with live handover notes which on-callers keep up-to-date as and when things come up.

Using shadow on-call to help new engineers learn

One of the biggest challenges we’ve faced is making it easy for new engineers to join the rotation, and for existing engineers to leave. We ask engineers to opt-in to on-call, because we know the disruption to life outside work isn’t something which works for everyone. But to encourage engineers to volunteer, we try to make the onboarding process as simple and convenient as possible. We’ve done this by introducing a shadow role, which lets engineers start being on-call without the pressure of leading incidents or needing to understand everything upfront.

Shadow on-callers are subject to the same expectations as a primary on-caller, but their main focus is to get comfortable with the processes, learn how our systems work, ask questions, and document the undocumented.

Asking questions and documenting the answers is one of the most important functions of the shadow. It’s easy to slip into situation where tribal knowledge rules, and you're only effective if you’ve been on-call for a long time. Six months ago, we were in this position, and it’s an uncomfortable place to be. Using shadow on-call together with high quality, operational runbooks has helped us find our way out.

Paying engineers fairly for being on-call

We pay engineers on-call £500 a week. We do this to recognise the inconvenience and disruption of being on-call, not as a payment for anyone’s time. Primary and shadow on-callers are paid the same.

We don’t pay per incident as we believe this can lead to some negative behaviours (we wouldn’t want to incentivise engineers to cause incidents!) Instead, engineers can take whatever time they need to account for the impact of being on-call. This ranges from coming in late or leaving early when they’ve lost small amounts of time, to taking multiple days off in lieu for full days of disruption.

Designing handovers to share information effectively

With our current schedule, we have three engineers on-call each week: one primary, one shadow, and one on-call during office hours. To help keep everyone on the same page, we keep a weekly live handover document containing a high level overview of what’s happened, what actions we’ve taken, and what actions we’ve deferred to a later date or different team.

This document is useful for engineers to refer to during their week on-call, and also as part of the weekly handover between separate rotations.

Using alerts to help the right people take the right action

We monitor Monzo using Prometheus to collect metrics, Alertmanager to handle the routing of alerts to the right places, and PagerDuty to get hold of people who need to take action.

We define an alert as something which needs a human response and use two severities:

Warning: A human response is required, but not urgently. These shouldn’t wake you at night, but should be looked at within eight hours.

Critical: An urgent response is required, and should get the attention of an on-caller immediately.

Handily, these severities map nicely to PagerDuty’s High/Low urgency notifications, which allow on-callers to determine how they’d like to be contacted for each. A common configuration we use is push notifications to the PagerDuty app for a warning and some combination of push, SMS and phone call for critical.

The wellbeing of an engineer on-call correlates strongly to the quality of their alerts. Too many alerts and you risk fatigue and apathy, whilst too few can lead to worse incidents that are caught later than necessary. Creating good alerts is hard, and involves a continuous process of creating, refining and removing alerts as the underlying systems and behaviours change.

Writing runbooks to guide engineers through incidents

We have a four-page document that explains everything you need to know.

We have no shortage of documentation, but finding and digesting documentation when something’s broken at 3am is nobody’s idea of fun. For this reason, we write runbooks. Runbooks are operational guides designed to walk you through a specific action in response to a specific problem. Typically, you’ll arrive at a runbook because an alert has sent you to it directly, but they’re also useful without that context too.

All of our runbooks follow this format:

Who can help? — Who can I talk to if I have questions with this process? Who can I escalate to?

Symptoms – How can I quickly tell that this is what is going on?

Pre-checks – What checks can I perform to be 100% sure this is a sensible guide to follow?

Resolution – What do I have to do to fix it?

Post-checks – How can I be 100% sure that it is solved?

Rollback – (Optional) How can I undo my fix?

With a consistent format and single task focus, runbooks are exactly what you want to guide you through an incident when you’re woken by a page.

Running retrospectives to improve

As with everything, there is always scope to improve. We run a retrospective every two weeks with the on-call team and representatives from our customer support team. We use this time to examine how we’re doing and identify areas for improvement.

Let us know what you think of our approach to on-call, and what's working well for you at your own organisations. If you're interested in joining our team of engineers and managers to tackle problems like this, we're hiring!